The Apparent Inevitability of Wireheading

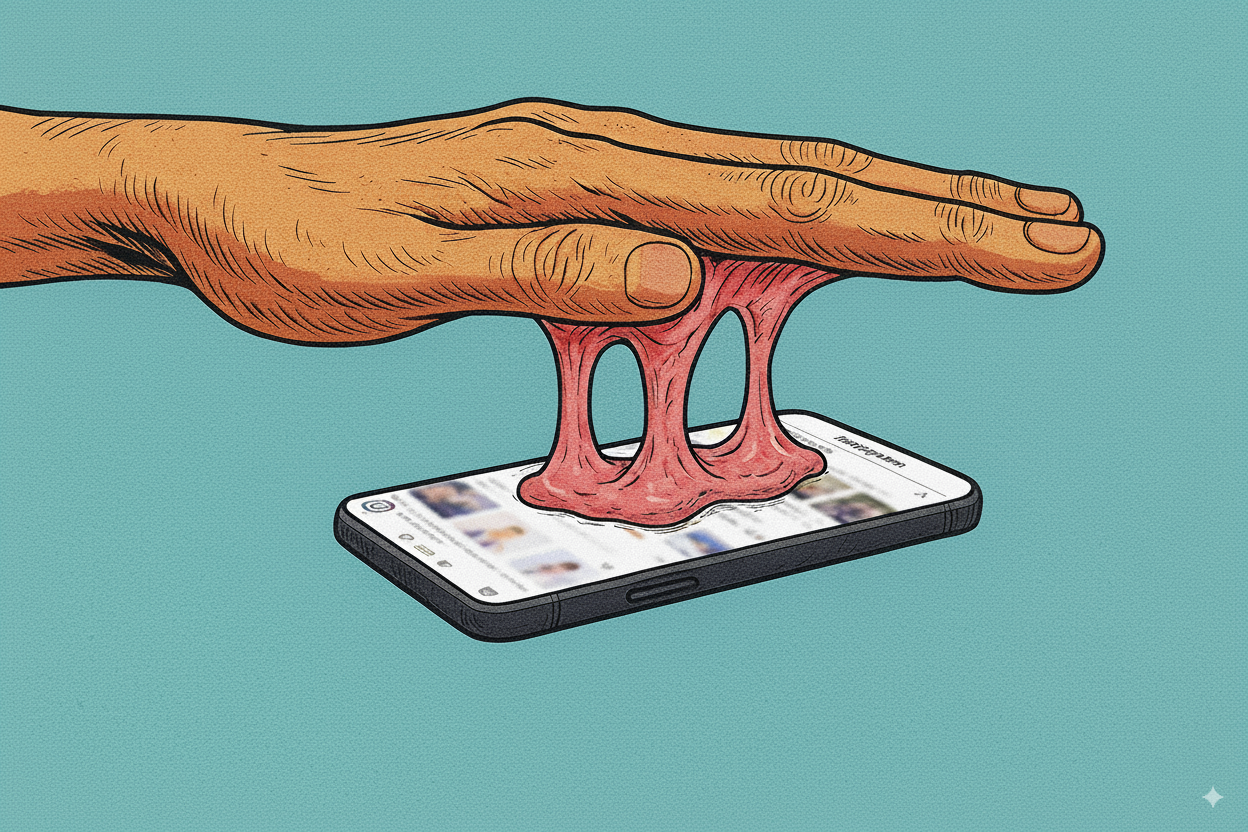

Massive AI systems are becoming increasingly adept at getting you to watch just one more video.

1984, George Orwell

Four weeks ago, in their quarterly earnings presentation, Meta announced that they have observed a 6% uptick in time spent on Instagram. This an app with more than 2 billion active users. The share price soared on the news.

A few weeks earlier, Google execs were on stage boasting an equally eyewatering number of their own. Total views of YouTube Shorts have reached 200 billion. A day.

Figures like these, as I see them, are primarily driven by two variables:

- How compelling the content on the app is

- How good the app is at personalizing the content feed to your liking

In fact, Meta credited the latter exactly. Improvements to the AI systems that drive content recommendation, they say, were the main driver of the Time in App uptick.

Very soon, though, the other variable will get turbocharged by AI, too. A surge of highly addictive AI-generated content is on the horizon. And then, I fear, Time in App goes hyperbolic.

Forgetting to Eat

If you spend any meaningful amount of time reading about AI, you’re familiar with the doomsday theories. They come with the territory. And most of the prominent warnings boil down to the same few components:

- We struggle to understand the current frontier models.

- We have no chance of understanding a so-called superintelligence, let alone control it.

- We die.

Now, I wouldn’t go so far as to call those three steps a consensus, but they comprise a prevailing theory in the space.

There are a few big IFs associated with this notion, though. The biggest of which is if superintelligence will ever be achieved. And the jury is still out on that front.

A couple of years ago, I heard a contrarian take that felt so feasible and so inevitable that it etched itself deep into my psyche. And I’ve found myself coming back to it more and more in recent months.

It was not contrarian in the sense that it arrives somewhere other than doom (sorry!), but its flavor of doom was certainly an outlier. The theory is called Wireheading.

While being interviewed on the Lex Fridman Podcast, hacker & founder, George Hotz was asked how he saw the AI endgame panning out. Hotz replied that he feared AI would cause humanity to amuse ourselves to death. To put it more viscerally, he said that humans will wind up “staring at [an] infinite TikTok and forgetting to eat.”

Okay, I realize that “forgetting to eat” part may read impossibly dramatic at first pass. And maybe it is. Maybe our social feeds never become that addictive.

Consider something a bit more benign, then. Let’s say social media becomes just 30% more addictive.

At 30% more addictive people aren’t yet forgetting to eat, but I’d posit to say that the extra 30% could worsen the adolescent mental health crisis, exacerbate the loneliness epidemic, and even accelerate the declining birth rate. Wouldn’t you? After all, a recent study showed Americans are already spending an average of 2 hours and 23 minutes on social media per day.

How about another?

All the major social media platforms deploy content recommender systems in an effort to optimize their feeds and drive up Time in App. In essence, they invest tons of money to get you to watch just one more video.

Before TikTok, none had ever been so successful. The app became a household name on the back of its fabled algorithm.

Despite ongoing efforts by US policymakers, TikTok’s secret sauce has never been fully revealed, but it goes something like this:

- TikTok observes what kind of content you view, like, share, and save

- Their system identifies other videos that fit that bill

- They show you more of those videos

TikTok’s UX—with no gaps between videos, no white space, no time to breathe—is the perfect sandbox for this sort of personalization experimentation. So perfect that Instagram with its Reels feature and YouTube with its Shorts built their own replicas.

Even so, a recommender system is nothing without a stream of fresh, compelling content to recommend. And for now, that stream, while extremely rapid (over 20M videos uploaded to YouTube per day) still runs at the speed of humans as it relies on real people to shoot, edit, and post those clips.

That reliance is disappearing. Thanks to falling costs and improving capabilities, AI generated content may soon be the dominant form of media on these platforms. Or, to stick with water metaphors, the floodgates are opening.

And, through a process known as Reinforcement Learning (RL), it seems inevitable that these videos will become more addictive than their human-created counterparts.

RL on Video

Back in the 2017, researchers at Google’s DeepMind developed the world’s best chess program, AlphaZero, using Reinforcement Learning. The researchers created the superhuman program, not by manually teaching it all the best moves. Instead, they simply outlined the rules of the game and told the algorithm it would receive a reward for a win and a penalty for a loss. Then they set it loose.

After just 9 hours of letting the program play chess against itself (a total of 44 million times), AlphaZero had gone from knowing “only the rules” of the game to surpassing the former computer chess champ, along with every human chess player that has ever lived.

That’s the power of RL.

Content creators grow their audience (and view counts) through a process that is not so dissimilar. They upload videos, observe how they perform, and iterate. These best practices are, of course, noticed by other creators and metriculate across the platform. That’s how we’ve ended up in a spot where all YouTube thumbnails look uncannily similar.

Imagine a world where, instead, someone deploys an AI model to upload videos to the social platforms. Like hundreds or thousands of videos per day. And then, using views and likes as its reward signal, the model updates its weights to become better at producing compelling content. Each tranche of videos would become ever so slightly more addictive, often times in ways that wouldn’t be readily discernible to a human observer.

Maybe the AI realizes that characters with brown eyes drive more engagement than ones with blue. Or that dog videos get more likes than their cat counterparts. Or that adding captions increase view time.

In any given video there are dozens and dozens of variables that can be adjusted, just like there are an absurd number of potential chess moves. But like with chess, with enough time and compute, I am confident that an AI model will be able to identify the optimal path to more engagement.

At this point, you might correctly point out that what I like to watch on YouTube or Instagram or TikTok is probably wildly different than what you do. One man’s brainrot is another man’s treasure, as they say.

Even this is barrier that can be broken down, though. With enough computing power at its disposal, AI systems could churn out enough variations that the videos themselves, like our feeds, could become essentially personalized to the viewer.

And then all bets are off.

The Tells are Disappearing

As recently as last year, people pointed out, often with an air of human superiority, that AI-generated content was easy to spot thanks to a roster of common mistakes that the models would make.

Most memorably, the models messed up human hands, like all the time. If you were unsure if an image was real, you could just count the fingers and you’d usually find your answer.

Well, as fascinating as the models’ capabilities have become, it’s quite terrifying that the signs of AI content are rapidly becoming nonexistent.

You, yes, you have almost certainly viewed a video that you were unaware was AI-generated. I’d actually guess that this happens on a weekly or even daily basis, depending on how heavy a social media user you are.

And that goes for even the most techno-literate among us. I work with generative AI on a daily basis, and, even for me, its becoming very hard to spot the fakes.

The discernibility used to act as something of a shield against the content’s virality. You could scoff and say “pshh that’s AI.” (Not that this scoff actually wiped it from your mental record and gave you your 15 seconds back, but I digress.) And maybe you’d be less likely to watch it again, or less likely to share it with a friend once you realized it was fake.

When you can longer tell if the video is AI, that shield disappears.

Stranger still, there is already an entire genre of AI-generated content where the creators don’t even try to hide that fact. And lots of people openly enjoy these artificially generated videos.

The guy that cuts my hair and I were talking recently about how addictive social media is, especially for kids—and how we see it getting worse in the age of AI. Because of that, he doesn’t let his son have an iPad. Yet even he, with all his apprehension, in his next sentence conceded that he really enjoys an AI-generated video series that features a gorilla vlogging about his fights with humans. It seems others do to. Videos like these have millions of views across platforms.

Follow the Money

It’s quite telling that Meta is still publicly touting its Time in App increases even on the heels of a bad few years of press. Thanks to books like The Anxious Generation and Careless People, I think most people, like my barber, have accepted that these apps are detrimental to our mental health, but the financial markets don’t seem to care.

For now, companies like Meta and Google are supported almost entirely by ad sales. And how do you sell more ads? Captivate your audience for marginally longer periods of time. Thus, they have every incentive to steal a few more minutes of your day (and brag about it to investors).

To make matters worse (and a huge reason why Wireheading feels so inevitable), the tech giants that own these platforms and advertising networks are some of the same firms that are on the leading edge of generative AI research. Thanks to the absurd cash flow that their ad businesses drive, the likes of Google and Meta are able to dump unprecedented sums of money into advancing generative AI.

I feel that a good framework for predicting the future is to look where the incentives lie. And, unfortunately for us, there are extreme financial incentives to build increasingly addictive user experiences.

Unless there’s a major social backlash, I fear that increased AI deployment will cause social media usage to continue to increase quarter over quarter, year over year.

From an outsider's perspective, the task of grabbing a few more minutes of users’ time seems way more achievable in the near-term (and way less nebulous) than building superintelligence. So I honestly won’t be shocked if Meta reports another 6% Time in App uptick in their Q3 earnings. In fact, I’d be shocked if it’s only another 6%.

Many Ways to Wirehead

Unfortunately for us, an increasingly addictive Instagram feed is not the only way we may end up Wireheading. It seems like it’s just one of many avenues that are revealing themselves.

I won’t go into it here, but there is an growing corpus of literature outlining how users of apps like ChatGPT are becoming addicted to conversing with the bot. In the most dramatic cases, these users are forming “relationships” with the AI or are being driven into pyschoses.

Some light reading on that front:

- She is in love with ChatGPT

- They Asked an A.I. Chatbot Questions. The Answers Sent Them Spiraling.

- He Had Dangerous Delusions. ChatGPT Admitted It Made Them Worse.

But while these more dramatic (and obviously dangerous) signs of Wireheading capture the headlines, the algorithms that curate our social media feeds are quietly humming in the background, getting ever so slightly smarter with each Like and Share.